Chitralekha Part I — The Question of Sin

“पाप व्यक्ति के वश होने का नाम है”

Sin is the name we give to being ruled by oneself.

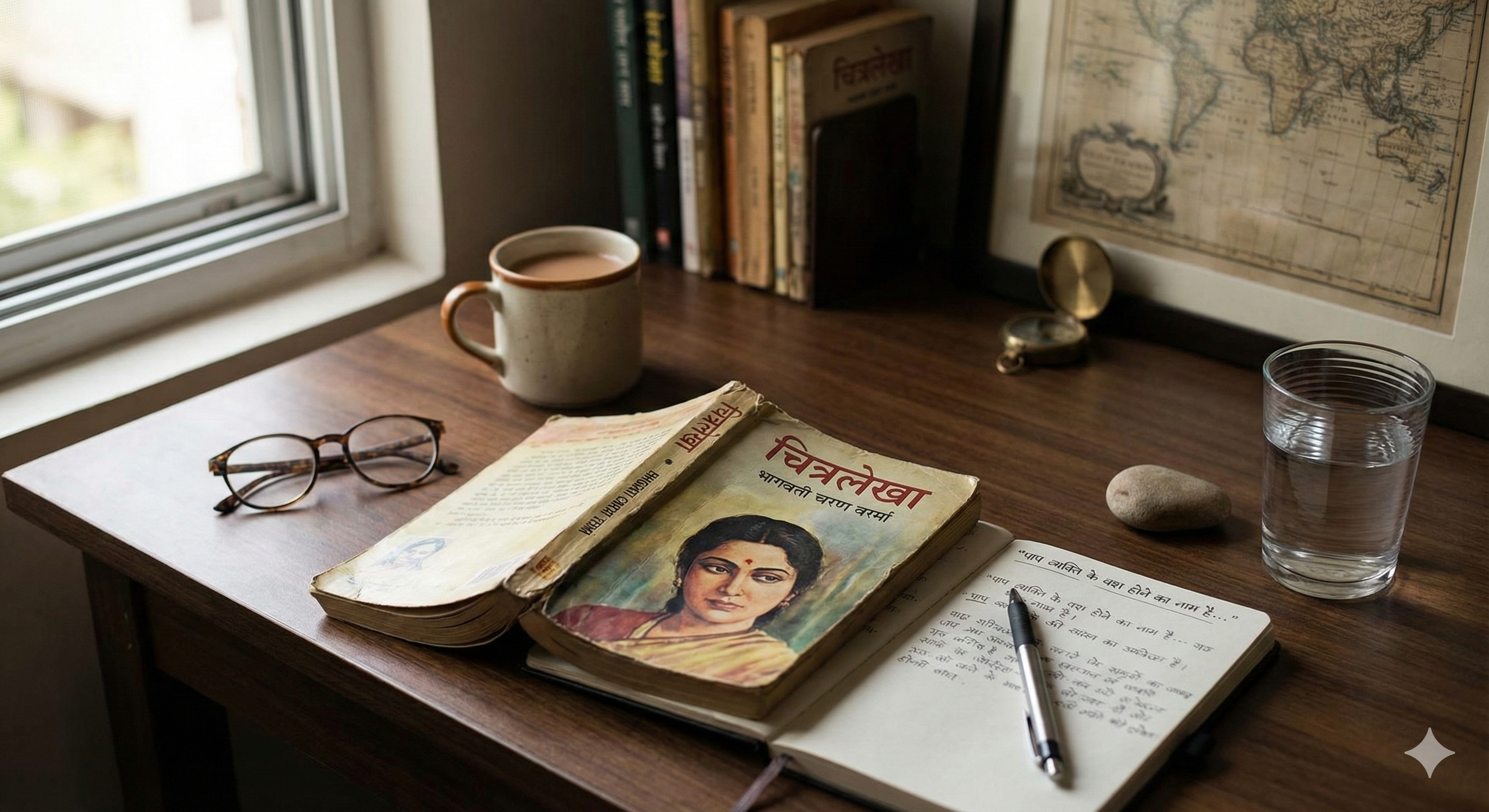

I read that line for the first time years ago, and it sat with me like a stone dropped into still water. At first, I didn’t quite understand it. I had always thought of sin the way most of us are taught to — as a list of forbidden acts, a moral boundary drawn by someone else. You cross it, you are guilty. You obey it, you are good. Simple arithmetic. Bhagwati Charan Verma’s Chitralekha cracked that arithmetic open for me.

It wasn’t the story that did it — though the story is graceful in its own right — but the unsettling quiet with which it asks that one question: What is sin? The question sounds harmless until you start answering it. Because the moment you do, you realize you’ve never really looked at it on your own terms. You’ve borrowed your definitions from religion, from society, from habit. Verma’s brilliance was to peel those layers away until the only thing left standing was you — your impulses, your discipline, your fear, your honesty.

When I picked up the book, I was not looking for philosophy. I was looking for a story, a distraction. But Chitralekha doesn’t distract; it confronts. It doesn’t moralize or scold — it simply places a mirror in front of you and asks whether you are the master of your actions or their servant.

The line I quoted above appears when Chitralekha, the courtesan, speaks almost casually, yet in those few words she overturns centuries of moral architecture. “Sin,” she says, “is not about what you do. It’s about whether you are in command of yourself while doing it.” That simple sentence shifted the floor under my feet. Because once you accept it, every convenient certainty collapses.

If sin is loss of control, then virtue is self-possession. And that means a monk who renounces the world because he fears temptation is not necessarily virtuous — he might just be weak. It also means a courtesan who lives in full awareness of her choices, without deceit or pretense, might be closer to innocence than we are willing to admit.

That reversal is what makes Chitralekha dangerous and beautiful. It insists that morality cannot be outsourced to custom or scripture. It must be lived consciously, one decision at a time.

When I first read the book, I remember closing it and sitting silently for a long time. The thought that “sin” might have nothing to do with rules but everything to do with awareness unsettled me. Because it meant I could no longer hide behind excuses. I could no longer say, “I did it because everyone does,” or “I was told to.” The only question that mattered was: Was I awake when I did it?

I began to see how much of my own life was spent half-asleep — doing things out of habit, emotion, or imitation. That line from Chitralekha began to whisper in those quiet in-between moments, when I was about to say something sharp or make a lazy choice. Are you in control, or are you being carried away? It was like being given a compass that points inward.

That is where this reflection really begins for me. Not in the courtesan’s chamber or the monk’s cave, but in the ordinary hum of a life where choices pile up silently — how we work, how we love, how we speak when no one is listening.

Verma’s question is not a literary one. It is practical. He’s not asking about abstract morality but about the simple discipline of living without being dragged by one’s own emotions or appetites. It sounds small, but it isn’t. The entire architecture of a peaceful life rests on that ability — to act without losing the reins.

I sometimes think of it this way: most of us believe we are steering our lives, but in truth, we are being steered — by anger, by vanity, by fear, by craving. We call those things “personality,” but they are often just habits that have taken charge. Chitralekha exposes that illusion with unsettling gentleness.

I will admit something: when I first understood what Verma meant, I didn’t feel enlightened; I felt cornered. Because once you see that your loss of self-control is the real sin, you start noticing how often it happens — how often you speak to defend your ego, not your truth; how often you chase something not because you want it, but because someone else has it. It’s an uncomfortable kind of honesty, but a necessary one.

That is what Chitralekha means to me at its core — not a novel about virtue and vice, but a quiet demand for awareness. Every act, no matter how noble or shameful, is measured by that one question: Who is in charge here — you, or your desire?

The rest of the novel, the interplay of monk and courtesan, disciple and general, is built on this foundation. It is a long conversation about control and surrender, disguise and truth.

And that’s where the next part of this reflection begins — with the woman at the center of it all, who, without sermon or pretension, taught me more about self-mastery than any philosopher could.