Chitralekha Part II —The Woman Named Chitralekha

“मैं पापिनी नहीं हूँ। मैं अपने जीवन की परिस्थितियों की देन हूँ। और मैंने इन परिस्थितियों से झूठ नहीं बोला है।”

I am not a sinner. I am a product of my circumstances. And I have not lied to them.

When I first met Chitralekha on the page, I expected her to be a symbol, as literature so often makes women — a vessel for other people’s guilt and redemption. But Verma denies us that comfort. He gives us a woman who refuses to fit into either category of purity or corruption. She is neither the seductress that ruins men nor the saint that reforms them. She simply is.

Chitralekha earns her living as a courtesan, but that word does not define her in Verma’s world; it is a profession, not a verdict. The grace of her character lies in her complete lack of pretense. She neither apologizes for who she is nor demands sympathy. When Beejgupta, the proud general, falls in love with her, she doesn’t play the part of temptation — she becomes a mirror for his contradictions.

There is a scene that stayed with me long after I finished reading. Beejgupta, torn between his attraction and his sense of morality, tries to justify himself. Chitralekha listens, then says quietly that his conflict isn’t with her at all; it’s with his own hypocrisy. “जो मन में है, उसे छिपाना ही पाप है,” she tells him — “To hide what is in your heart, that alone is sin.”

That line cut through every moral disguise I’d ever seen — the way people pretend to be virtuous because they fear judgment more than they value truth. Her words are not defiance; they are clarity. In her world, honesty is the only purity that counts.

What struck me even more was how Verma refuses to glorify her suffering or make her redemption a moral spectacle. Chitralekha does not seek to escape her life; she seeks to understand it. That difference is everything. Most of us spend our lives trying to fix our circumstances instead of understanding them. She does the opposite. She looks at her reality without embellishment, and in doing so, becomes larger than it.

I remember thinking: perhaps freedom is not about changing where we stand, but about changing how we stand there. Chitralekha’s freedom is internal — not granted by society or taken from it, but earned in her refusal to lie to herself.

What fascinates me most about her is that she does not reject desire; she simply refuses to be its prisoner. In a world where both religion and hedonism define themselves by extremes, she occupies the middle ground — where awareness makes desire neither shameful nor sacred, only human.

That balance reminded me of something I’d read later in the Gita, where Krishna tells Arjuna that desire itself is not the problem; attachment is. Chitralekha lives that philosophy long before the reader recognizes it. She neither renounces nor indulges; she understands.

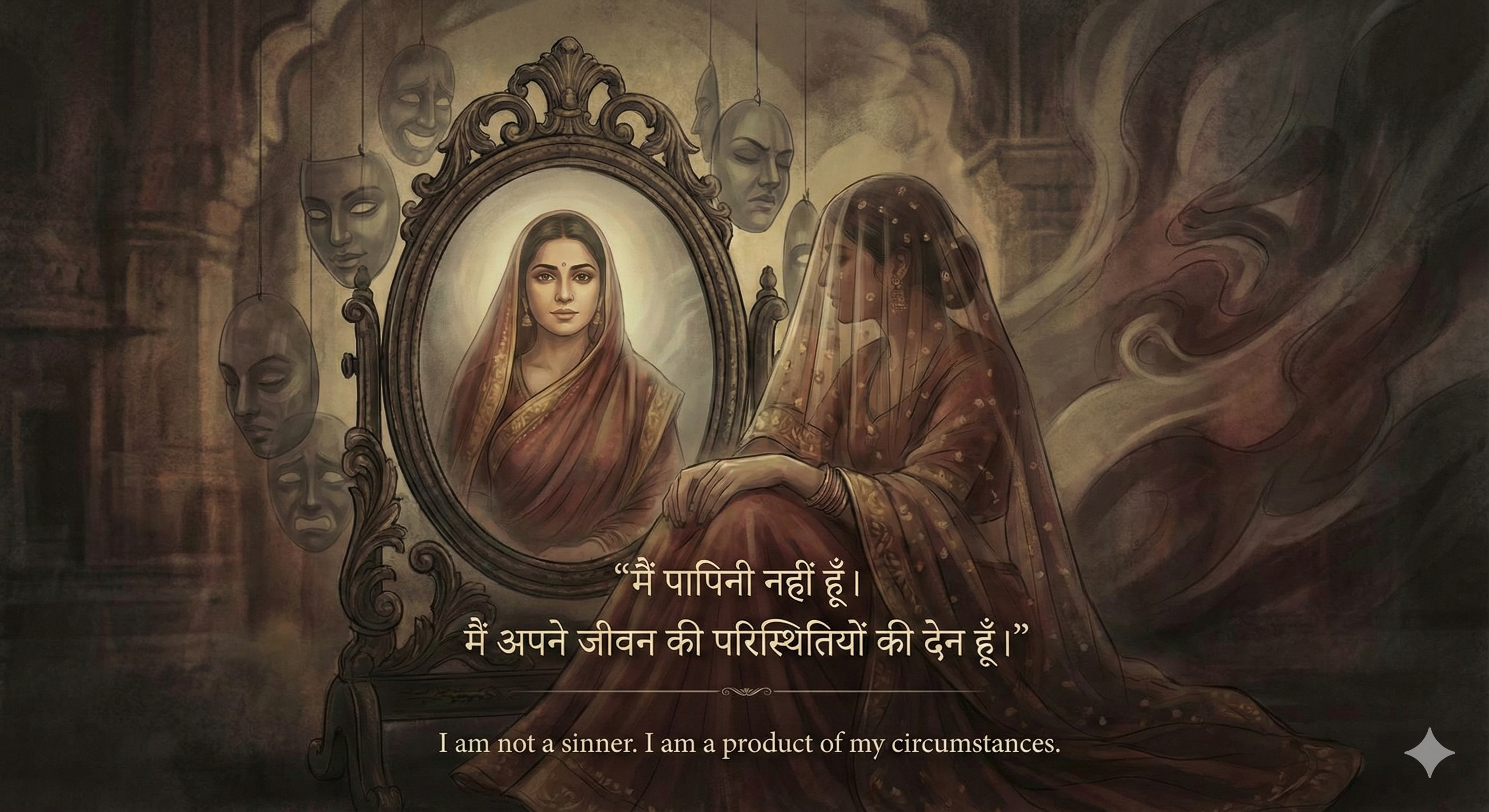

When I think of her now, I realize she embodies something even rarer than virtue — self-knowledge. She sees herself clearly, and in that clarity, she finds dignity. We often assume dignity comes from purity, but Verma suggests the opposite: it comes from truth.

The older I grow, the more I see why her character unsettled the moral order of her time — and still does. Because if a courtesan can be virtuous through awareness, then virtue itself must be redefined. That is a terrifying thought for any society built on moral hierarchies.

To me, Chitralekha is not a rebel; she is a realist. She lives with eyes open. And once you have seen the world through her eyes, it becomes impossible to unsee the falseness of so many masks we wear — the disciplined ascetic who hides pride under humility, the lover who calls his obsession devotion, the man who mistakes fear for conscience.

Every character in the novel orbits around her clarity. Beejgupta’s turmoil, Shwetank’s confusion, even Kumbh Muni’s detachment — all of it gains meaning because she exists. She is the still point in their storm, and by her presence, each of them must face himself.

When I look back on my first reading, I realize she was less a character and more a challenge. Verma built her not to be admired but to be confronted. Through her, he asked each of us a quiet, devastating question: If you stripped away every disguise, every inherited belief, who would you really be?

I didn’t have an answer then. I still don’t, not fully. But I’ve learned that the question itself is the point.

Because the moment you stop fearing what you’ll find under your masks — that moment, you begin to live truthfully.

And that’s where the next thought leads — into the uneasy relationship between desire and detachment, and the way Chitralekha blurs that boundary until it disappears.