Chitralekha Part III - Desire and Detachment

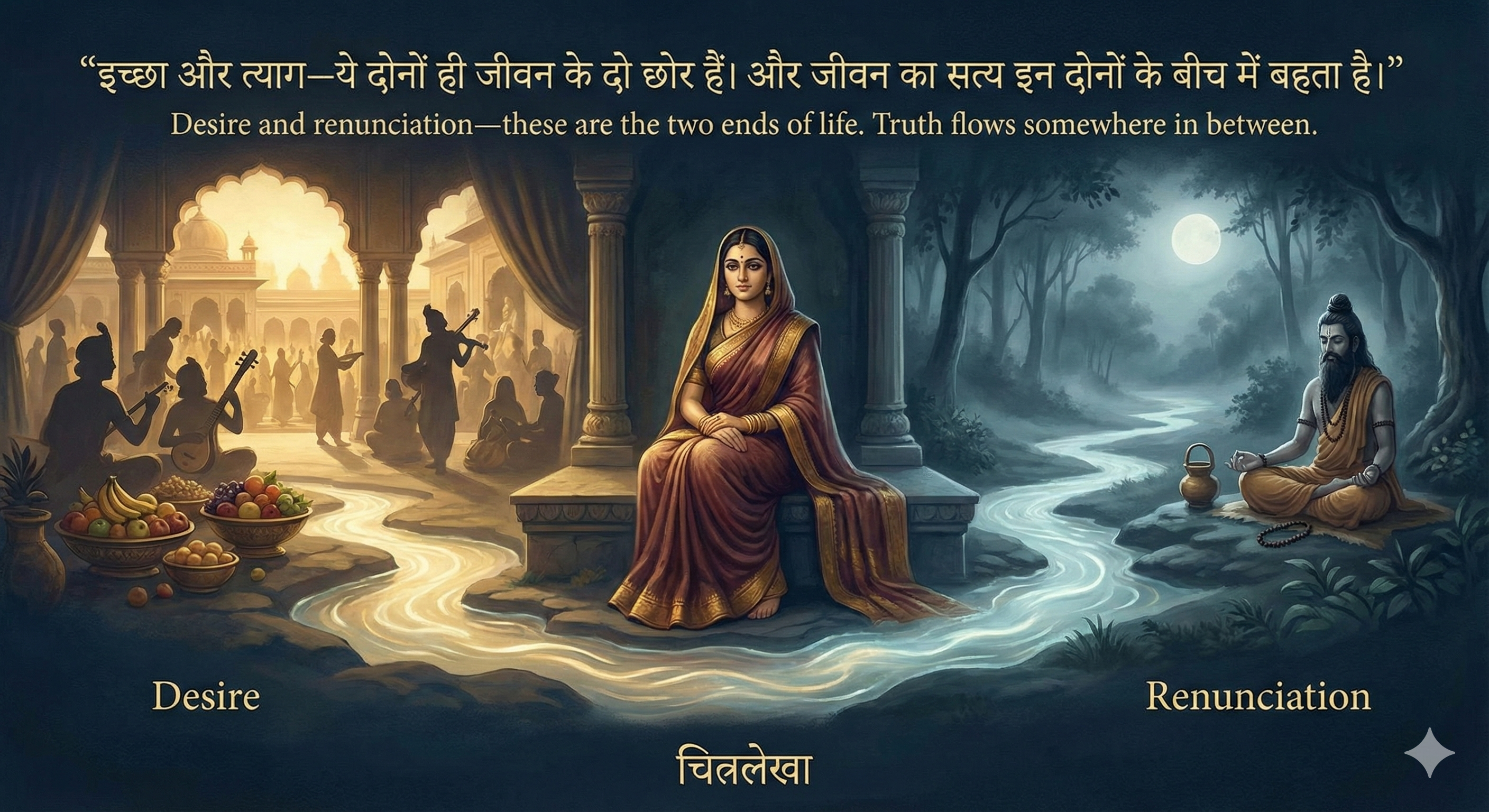

“इच्छा और त्याग—ये दोनों ही जीवन के दो छोर हैं। और जीवन का सत्य इन दोनों के बीच में बहता है।”

Desire and renunciation—these are the two ends of life. Truth flows somewhere in between.

I have always found that line haunting. It sounds simple enough, almost poetic, but like everything else in Chitralekha, it hides a quiet rebellion. Verma refuses to choose sides in that ancient quarrel between the world and the monastery. He does not tell us to run from desire, and he does not tell us to drown in it. He tells us to stay awake in its midst.

For most of my life, I believed detachment meant denial — that to be spiritual was to turn away from the senses, to close the door on temptation. But reading Chitralekha taught me that denial is just another form of bondage. When you suppress something, it does not vanish; it waits. And when it returns, it comes back sharper, demanding payment for every moment you pretended not to see it.

Verma’s world is full of characters who try to control life by rejecting it. Kumbh Muni retreats to the forest, certain that peace lives only in isolation. Beejgupta hides behind his armor of discipline, as if duty could protect him from his own heart. Shwetank, the naïve disciple, believes purity is a matter of avoidance. And then there is Chitralekha, standing among them like a question mark, reminding them that life cannot be controlled by fleeing it.

She lives in the world fully — she laughs, she earns, she loves — and yet she remains untouched in a way none of them can manage. It is not because she is indifferent, but because she is present. That difference, I think, is what Verma means when he writes that truth flows between desire and detachment. One extreme burns you, the other freezes you. Only awareness lets you walk the narrow ground between them.

When I began to think about it, I realized how much of our moral conditioning comes from fear. We are afraid of what we might become if we give in to our hungers, so we build fences around them. Religion calls it discipline, society calls it decency, but at its heart, it’s fear — the fear of losing control, the fear of ourselves. Chitralekha doesn’t mock that fear; it understands it. But it also shows us that fear cannot lead to freedom.

There’s a moment in the novel when Kumbh Muni tells his disciples that the world is full of traps. He means lust, greed, pride — the usual list. But when the same disciples meet Chitralekha, they see something that doesn’t fit that definition. She has all the things the sage warned them about — beauty, wealth, admiration — and yet she is serene. Her calm exposes the flaw in their teacher’s warning. The trap was never the world; it was the inability to stand steady within it.

That realization hit me hard. How often do we retreat from something not because it is wrong, but because it overwhelms us? And how often do we call that retreat “virtue”? I’ve seen people avoid love and call it discipline, avoid risk and call it prudence, avoid truth and call it diplomacy. I’ve done it myself more times than I care to admit.

But Chitralekha showed me that real discipline is not the absence of feeling — it is the ability to feel without drowning. It’s the difference between steering a boat and being carried away by the current.

In that sense, detachment isn’t about distance; it’s about mastery. You can be in the thick of desire and still be detached if you remain your own master. And you can live in a cave and still be enslaved if your fears control you.

I began to notice that principle everywhere — in work, in relationships, in ambition. The problem was never wanting something; the problem was wanting it so badly that it owned me. And so I started asking myself, quietly: Can I want this without needing it? Can I care without clutching?

Those questions changed everything. They made me less reactive, less afraid. They taught me that desire is not an enemy; it’s a teacher. It shows you where you’re still weak, where you still mistake craving for purpose.

That’s why Verma’s view feels closer to a spiritual realism than moral philosophy. He does not glorify restraint, nor does he condemn pleasure. He writes as someone who has watched life closely enough to know that both asceticism and indulgence can become prisons. The only freedom is awareness — the capacity to see your desire clearly and yet remain unshaken.

Reading those pages, I felt something loosen inside me. It was as if the book had quietly absolved me of guilt — not by saying everything is allowed, but by saying: You are allowed to be human. That sentence alone can lift years of self-reproach.

And once you accept your humanity, something unexpected happens — you begin to grow beyond it. Because what you no longer deny, you can finally understand.

That, to me, is the essence of Chitralekha’s wisdom: detachment that blooms from understanding, not fear.

The next step in my journey with the book came when I began to see how deeply its vision echoes something far older — the quiet balance of the Bhagavad Gita.