Chitralekha Part IV - In the Company of the Gita

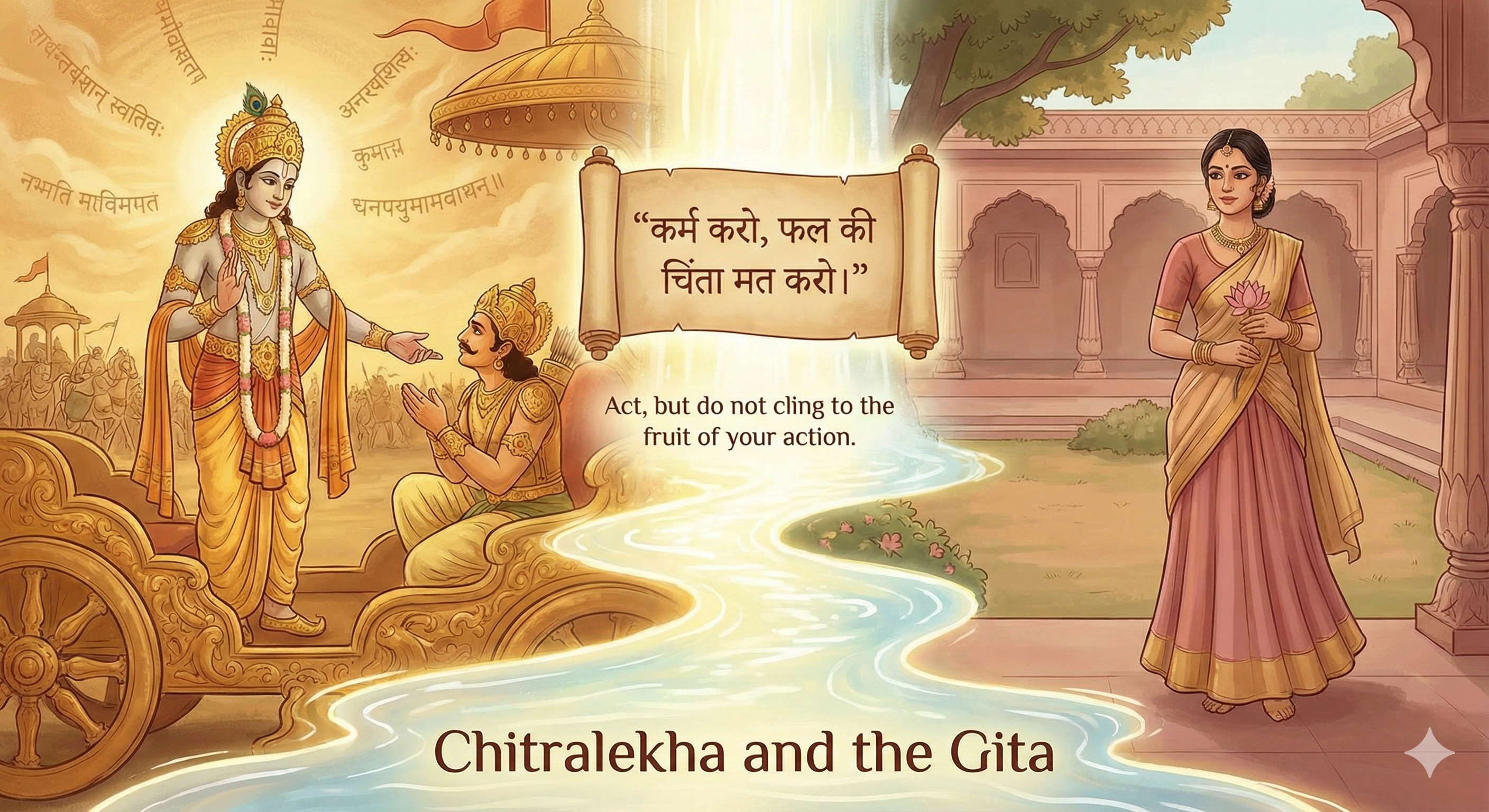

“कर्म करो, फल की चिंता मत करो।”

Act, but do not cling to the fruit of your action.

It’s a line we all know — the heartbeat of the Bhagavad Gita. We hear it so often that it risks becoming background noise, a moral slogan we recite without listening. But when I read Chitralekha, I heard it again as if for the first time. Not as instruction, but as recognition.

Because Verma’s world is not built on temples or wars. It is built on the same battlefield that Arjuna stood upon — the one inside the mind. The war between impulse and awareness, between duty and desire, between what we are told to be and what we know ourselves to be.

When Krishna tells Arjuna to act without attachment, he’s asking for something almost impossible: engagement without obsession. It sounds divine because it is so rare in human life. But Verma, writing centuries later, takes that divine instruction and grounds it in flesh and thought. He shows us what it looks like in practice — not on a battlefield, but in the everyday choices of people trying to live truthfully.

Chitralekha, in her own quiet way, lives the Gita more faithfully than the ascetics who preach it. She acts without clinging. She does her work, feels love and pain and weariness, and yet does not define herself by any of it. She reminds me of Krishna’s counsel to Arjuna: “Yoga is balance in action.”

When Beejgupta loves her, he is torn apart by guilt because he thinks love itself is sin. But the sin isn’t the love — it’s his confusion. He wants passion and purity both, and because he can’t reconcile them, he suffers. Watching him, I realized how often we do the same thing: we try to live according to borrowed definitions of good and evil, and in doing so, lose our natural rhythm.

The Gita says: do what you must, but without being bound by it. Verma shows us what that looks like — through a courtesan’s calm, a general’s torment, a monk’s blindness. The spiritual idea and the human drama finally meet.

As I reread both texts side by side, I began to see their shared center — the insistence on self-mastery as freedom. The Gita calls it samatvam, equanimity. Verma calls it apne vash mein rehna, to be in control of oneself. The language differs, but the heartbeat is the same.

When I was younger, I misunderstood the Gita as a manual for detachment — a call to withdraw from desire and emotion. But reading it through Chitralekha, I understood that detachment is not withdrawal; it is participation without bondage. You can love deeply, work fiercely, dream boldly — as long as you don’t surrender your center.

In one passage, Chitralekha says something that could have come straight from Krishna himself:

“जीवन का सौंदर्य तभी तक है जब तक हम उस पर अधिकार रखते हैं। जब जीवन हम पर अधिकार जमा ले, तब वह पाप बन जाता है।”

Life is beautiful only as long as we command it. When life begins to command us, it becomes sin.

That, to me, is karma yoga stripped of scripture and made human. No theology, no divine revelation — just the same truth expressed through experience.

I remember thinking how revolutionary this was, especially for a novel written in the 1930s. It dared to claim that holiness has nothing to do with robes or rituals; it has everything to do with how honestly you live your impulses. It placed the courtesan and the monk on the same moral plane, judged only by awareness, not appearance.

Over time, I began to see the Gita not as a text of religion but as a text of mental discipline — the art of remaining steady amid motion. Verma seemed to have intuited that centuries ago. His Chitralekha doesn’t renounce life; she embodies that steadiness in the thick of it.

And somewhere along the way, I realized that the divide between philosophy and life is itself an illusion. We treat the Gita as scripture and Chitralekha as fiction, but they are both mirrors — one cosmic, one human. Both ask the same question: Can you live without becoming a prisoner of what you love or fear?

That question stayed with me, like a quiet hum in the background of my days. It would rise when I lost patience, when I compared myself to others, when I chased something too hard. It reminded me that detachment isn’t indifference — it’s intimacy without possession.

And that understanding led me beyond India’s scriptures — to something strangely familiar in a completely different tradition: the calm of the Stoics, those old Romans who believed almost the same thing, in a different tongue.