Chitralekha Part V - In the Company of the Stoics

“हम अपने कर्मों के स्वामी हैं, परिस्थितियों के नहीं।”

We are masters of our actions, not of our circumstances.

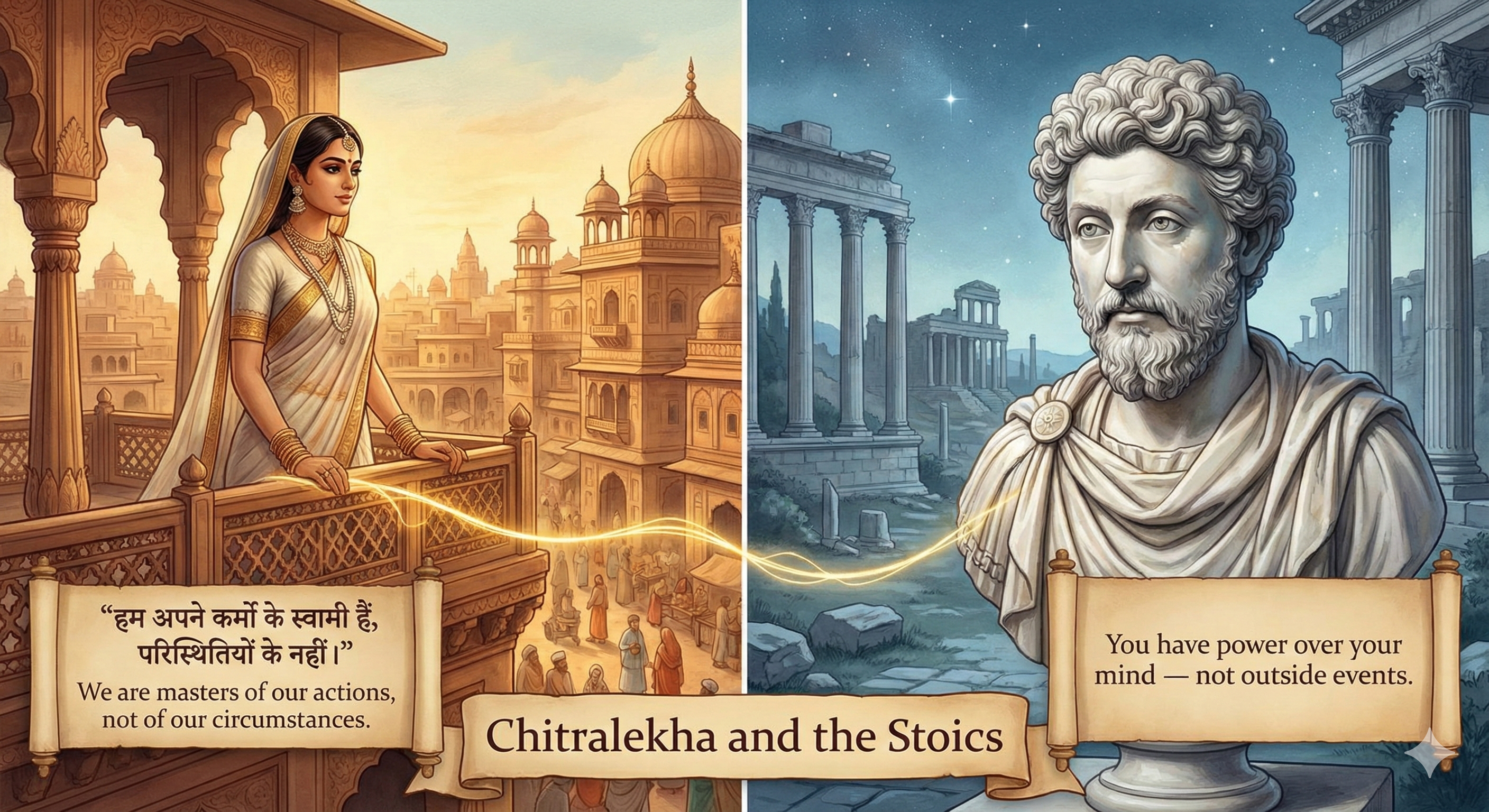

I didn’t think a Hindi novel from 1934 could remind me of Marcus Aurelius — a Roman emperor writing to himself nearly two thousand years earlier. Yet as I reread Chitralekha, I kept hearing faint echoes of the Stoics, those stern philosophers who believed that peace lies not in controlling the world but in governing oneself.

Marcus wrote in his Meditations: “You have power over your mind — not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.” When I first read that, I thought it was a kind of self-help mantra. But Verma’s world gave it flesh. He took the abstraction of Stoic discipline and showed me what it feels like to live by it — with all its beauty and difficulty.

Chitralekha, once again, becomes the bridge. She is what the Stoics would have called a sage, though she would never use the word. She accepts her life without resentment, meets desire without panic, and faces judgment without defense. Her strength lies in her refusal to be shaken. The world around her moves — men fall in love, monks fall from grace, power rises and collapses — and she stands quietly, like a tree in the wind.

“मैं अपने भाग्य की मालिक नहीं हूँ, पर अपने आचरण की ज़िम्मेदार ज़रूर हूँ।”

I do not control my fate, but I am responsible for my conduct.

That line could have come from Epictetus, the Stoic slave who taught that freedom is internal. Verma might never have read him, but both men understood the same law of human nature: peace comes not from the absence of turmoil, but from the absence of surrender to it.

When I read those words in my twenties, they sounded noble. When I reread them years later, after disappointments, mistakes, and regrets, they sounded practical. Life had proven their truth. You cannot control the way people behave, the luck you receive, or the losses that come uninvited. But you can control the way you meet them.

In that sense, Chitralekha is a Stoic text in disguise — one that speaks in the idiom of love and shame instead of reason and fate. Every time Beejgupta blames the world or his desires for his downfall, Chitralekha reminds him that the enemy isn’t out there. It’s the storm inside.

There is a passage where she tells him:

“मनुष्य अपनी कमजोरी को परिस्थिति का नाम दे देता है।”

Man calls his weakness circumstance.

That single sentence, to me, captures the essence of Stoicism more clearly than any Western philosopher ever managed. We invent excuses for our lack of mastery. We call them fate, destiny, environment, emotion. But what we truly lack is discipline — the steady inner strength to respond rather than react.

Reading those lines, I felt both humbled and freed. Because if peace depends on self-mastery, then I am no longer a victim of what happens to me. I am responsible, always. That is terrifying — but also liberating.

The Stoics called this condition apatheia — not the absence of emotion, but the freedom from being ruled by it. And that’s precisely what Verma means when he writes that sin is being “वश में होना,” under someone or something’s control. Whether that “someone” is anger, lust, pride, or fear — the result is the same: you become smaller than yourself.

Chitralekha never surrenders that center. She doesn’t pretend she feels nothing — she laughs, weeps, argues, and loves — but she never forgets who she is in the process. That, to me, is her quiet greatness. It’s not purity; it’s equilibrium.

Over time, I began to notice how this principle applies to ordinary life. The more you practice it, the lighter you become. You stop expecting perfection — from others, from yourself. You begin to focus on conduct, not outcome. You find yourself pausing before reacting. And that pause, small as it is, becomes the doorway to peace.

That’s why Chitralekha doesn’t feel ancient to me. It feels timeless. Its wisdom isn’t rooted in culture or creed; it’s rooted in how the human mind works. We are still fighting the same battles — between impulse and judgment, emotion and clarity, want and wisdom. Verma’s characters might wear robes or armor, but their inner struggles are ours.

And yet, there’s something in the novel that even Stoicism doesn’t reach — something more tender, more human. Because while the Stoics often sound like they wish to escape emotion, Verma embraces it. He allows his characters to feel everything, to stumble and ache and long, but he asks them to stay conscious while doing so.

That’s where he goes beyond philosophy and enters life.

In Stoicism, reason is the guide. In Chitralekha, awareness is. Reason belongs to the mind; awareness belongs to the whole being. It’s what allows you to experience the world without being devoured by it.

I think that’s why Verma’s writing moves me more than the Stoics’ aphorisms ever did. Because his truth is not carved in stone; it breathes. It understands our frailty, forgives it, and then quietly points us toward strength.

And as I kept tracing this thread — from the courtesan’s calm to the warrior’s confusion to the monk’s detachment — I began to see another pattern emerging: Verma’s world isn’t just Stoic or Gita-like. It’s also profoundly existential — concerned not with what rules to follow, but with how to live truthfully in the absence of rules.

That realization led me to the next bridge in this long conversation — from India’s forests and Rome’s stoas to the lonely cafés of twentieth-century Europe, where another kind of philosopher wrestled with the same question in a darker key: What does it mean to choose?