Chitralekha Part VI - The Solitude of Choice

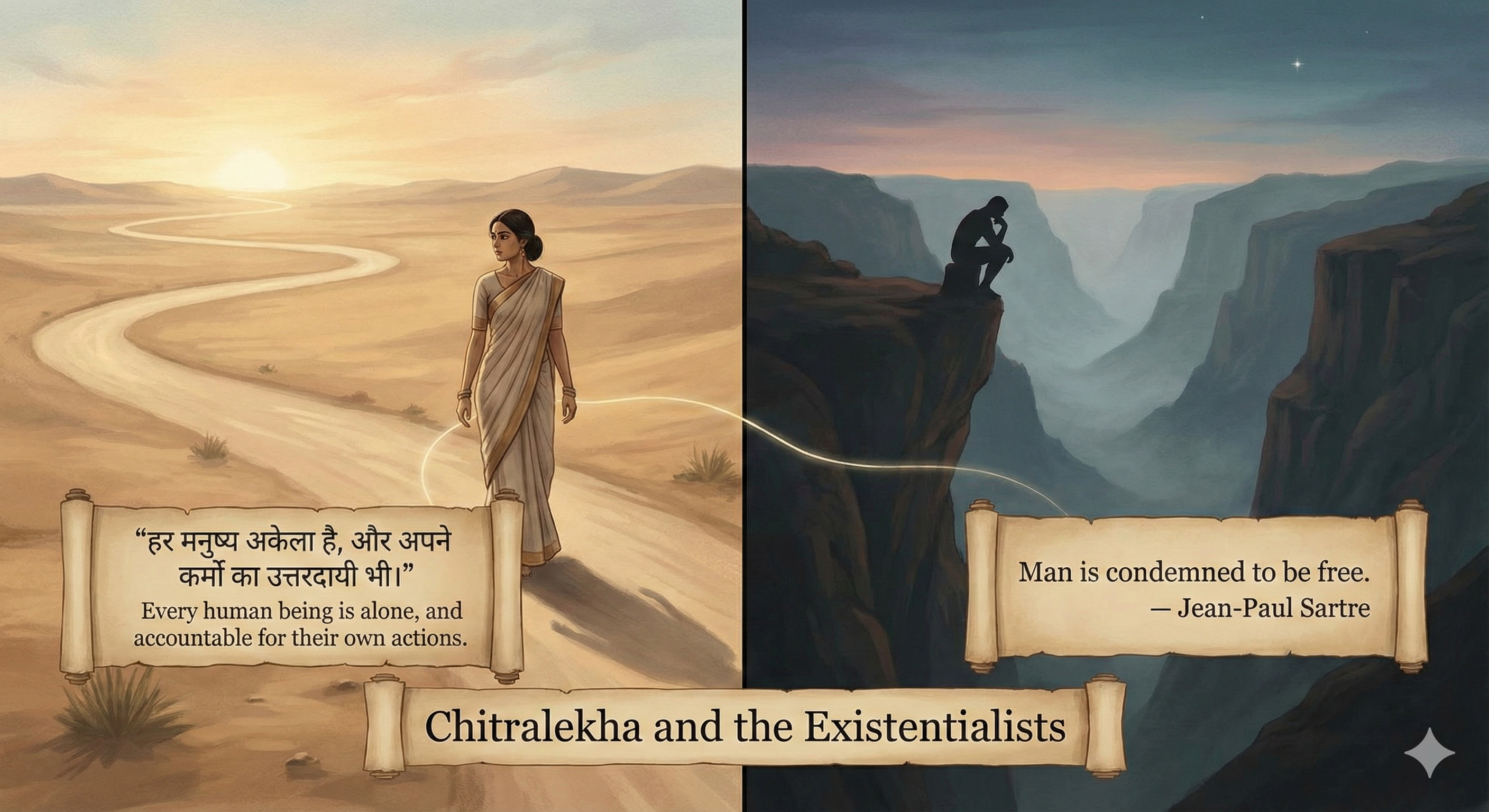

“हर मनुष्य अकेला है, और अपने कर्मों का उत्तरदायी भी।”

Every human being is alone, and accountable for their own actions.

That line appears late in the book, almost hidden in a quiet dialogue, but it struck me like a bell. It’s the point where Chitralekha stops being a story about morality and becomes something more daring — a meditation on freedom.

By then, the characters have all been stripped bare. The monk’s renunciation is revealed as pride in disguise, the warrior’s discipline as fear of passion, the disciple’s innocence as ignorance. And standing among them, Chitralekha remains the only one unmasked — not because she is flawless, but because she no longer pretends.

She accepts that she is alone. That no guru, no lover, no god will carry the weight of her choices. That realization doesn’t crush her; it steadies her.

In that moment, Verma reaches the same summit that the existentialists of the twentieth century were climbing from the opposite side. Sartre would later write, “Man is condemned to be free.” Condemned, because with freedom comes responsibility — the knowledge that every choice defines you, and there is no one to blame. Verma’s Chitralekha arrives there without European philosophy, through the simple clarity of lived truth.

“मनुष्य को अपने कर्मों के साथ अकेले चलना पड़ता है।”

A person must walk alone with their actions.

When I first read that, I remember feeling both comforted and afraid. Comforted, because it confirmed something I had always sensed — that life’s meaning isn’t handed to us. Afraid, because it meant there’s no refuge in excuses.

We like to think our choices are forced by circumstance — by family, by culture, by time. But Verma refuses that soft landing. His characters face the fact that every decision, even the act of surrender, is a choice. And once you accept that, the ground shifts.

I think that’s why the novel feels modern, even radical. It refuses to divide the world into saints and sinners. Instead, it divides it into those who choose consciously and those who drift unconsciously.

For me, this was more than philosophy. It was a mirror held up to the way I lived. I began to notice how often I moved through life on autopilot — choosing not out of awareness, but out of habit or fear. When you start to see that pattern, you can’t unsee it.

There’s a moment in the book when Shwetank, the disciple, realizes that his pursuit of purity has made him cruel without knowing it. He has judged others so long that he can no longer see his own rigidity. That passage made me pause because it described me more than I wanted to admit. I’ve often mistaken restraint for virtue, silence for wisdom. But both can be cowardice in disguise.

Verma’s greatest insight, I think, is that morality without self-awareness is just another form of vanity. We wear it to feel superior. But when awareness enters, vanity burns away. What remains isn’t morality — it’s honesty.

That honesty is frightening at first. It means taking responsibility not only for what you do, but for what you feel — your anger, your jealousy, your hunger, your love. You can’t blame them on anyone else. You can only meet them, learn from them, and decide what to do next. That’s the solitude of choice.

But that solitude isn’t empty. It’s luminous. It’s the space in which you finally stop performing for the world and start listening to yourself. It’s the silence before every genuine decision.

I think that’s what Verma was after all along — to show that sin isn’t about breaking rules, and virtue isn’t about following them. Both are about whether we live awake or asleep. To live awake is to choose — even when it hurts, even when no one understands.

When I finished the book, I remember closing it with a strange calm. I didn’t feel inspired in the usual sense; I felt sober, grounded. The noise of self-justification had fallen quiet.

It reminded me of something I once read from Camus — that the only real question is how to live without appeal, meaning without leaning on borrowed meaning. Chitralekha lives that question more than she answers it.

In that sense, she is not just a character — she is an invitation. To stop hiding behind our roles. To stop explaining our choices to an invisible jury. To accept that freedom and solitude are the same thing.

And once you accept that, something unexpected happens — life starts to make sense again. Not because it becomes easier, but because it becomes yours.

That realization led me to the final thought this novel left behind — what it means, after all this reflection, to live a better life.