Chitralekha Part VII - What It Means to Live Well

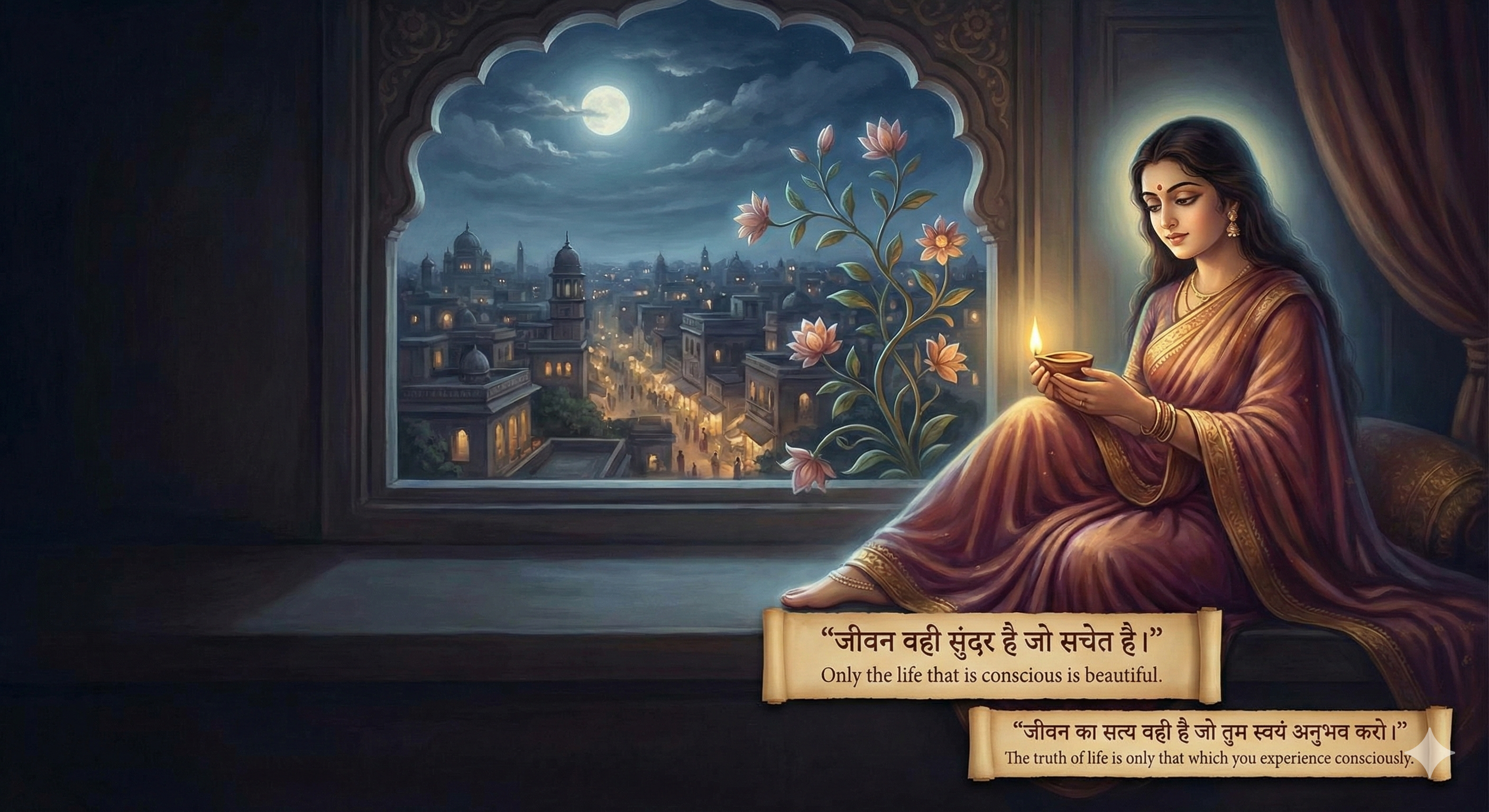

“जीवन वही सुंदर है जो सचेत है।”

Only the life that is conscious is beautiful.

Every time I return to Chitralekha, I find that line waiting for me like an old friend — quiet, unassuming, but always new. I think it’s because it contains, in ten words, the essence of everything Verma was trying to say: awareness is the only virtue that endures.

We live in an age obsessed with achievement — titles, salaries, validation, applause. We mistake motion for meaning, speed for success. But Verma, writing almost a century ago, reminds us that the true measure of a life has nothing to do with how far you go; it has everything to do with whether you are awake while walking.

That sounds simple, but it’s the hardest thing in the world. Awareness requires discipline, and discipline is not rigidity. It’s a kind of tenderness with yourself — a refusal to drift. It means stopping long enough to ask, Why am I doing this? Not once in a lifetime, but a hundred times a day.

For a long time, I thought the opposite of sin was goodness. Now I think it’s awareness. Because when you are aware, you cannot lie to yourself for long. And when self-deception dies, virtue grows naturally, like a plant finding sunlight.

This, I believe, is what Verma meant when he wrote that sin is being under someone else’s control — even if that “someone” is your own desire. To live well, then, is not to live perfectly. It is to remain in command of yourself through imperfection. To stay steady even as you stumble.

In my own life, that has meant learning to pause — to catch myself before reacting, to listen before answering, to choose before wanting. It’s astonishing how much peace hides inside that pause. The world doesn’t slow down, but your relation to it does. You stop being flung from one emotion to the next. You begin to act from intention instead of reflex.

It also means forgiving yourself for the days you fail — because awareness isn’t a destination; it’s a practice. There are mornings when I wake calm and centered, and by afternoon I am restless, angry, anxious. I used to call those failures. Now I call them reminders. Every lapse is just another invitation to return to myself.

What Chitralekha taught me — what I now try to remember — is that morality is not a ladder we climb; it’s a balance we maintain. Lose that balance, and we fall into sin, not because we’ve broken a rule, but because we’ve abandoned our own consciousness.

“पाप क्या है और पुण्य क्या है? व्यक्ति के वश में रहने का नाम पुण्य है, और वश से बाहर जाने का नाम पाप।”

What is virtue and what is sin? To remain in control of oneself is virtue, and to lose that control is sin.

That line has followed me like a compass. It appears simple, but every time I test it against life, it holds.

In relationships, it means loving without possession.

In work, it means striving without greed.

In solitude, it means being content without escape.

It’s astonishing how this single definition can untangle so many confusions. It doesn’t ask you to be holy or detached or ascetic. It only asks you to be awake. To remain your own master — not in a grand, heroic way, but in small, invisible ways that make up the fabric of a day.

When I think of living well now, I don’t think of achievement or even happiness. I think of steadiness. A quiet steadiness that allows you to feel everything — joy, grief, desire, fatigue — without becoming their captive.

That steadiness doesn’t come from rejecting the world; it comes from being fully in it. From accepting that you will be tempted, hurt, exhausted, and yet choosing not to let those things define you.

Sometimes, late at night, I imagine Chitralekha sitting by a window, looking out at a city that still judges her. And I think of how calm she must feel — not because the world has changed, but because she no longer needs it to. She has become her own witness.

That, to me, is the true reward of awareness: you stop living for the eyes of others. You stop performing. You begin to live quietly, honestly, inwardly — and that quiet becomes your strength.

In our time, when distraction is constant and outrage easy, her lesson feels almost radical. To be aware is to resist. To be still is to be strong. To be self-possessed is to be free.

So when I ask myself now what it means to live well, I think of her words. I think of Kumbh Muni’s question — What is sin? — and I realize it is not a question about morality at all. It’s a question about mastery. About how to remain the pilot of one’s own ship while crossing seas that will never calm.

Living well, then, is simply this: to act with intention, to love without illusion, to see clearly, and to stay awake.

That is the life Verma asked of us through Chitralekha.

And in the quiet moments of my own life — between one impulse and the next — I still hear her whisper:

“जीवन का सत्य वही है जो तुम स्वयं अनुभव करो।”

The truth of life is only that which you experience consciously.

And in that whisper, the noise of the world fades — and something simple, almost sacred, remains.