The Quiet Weight Of Orders - Part 2 of 4

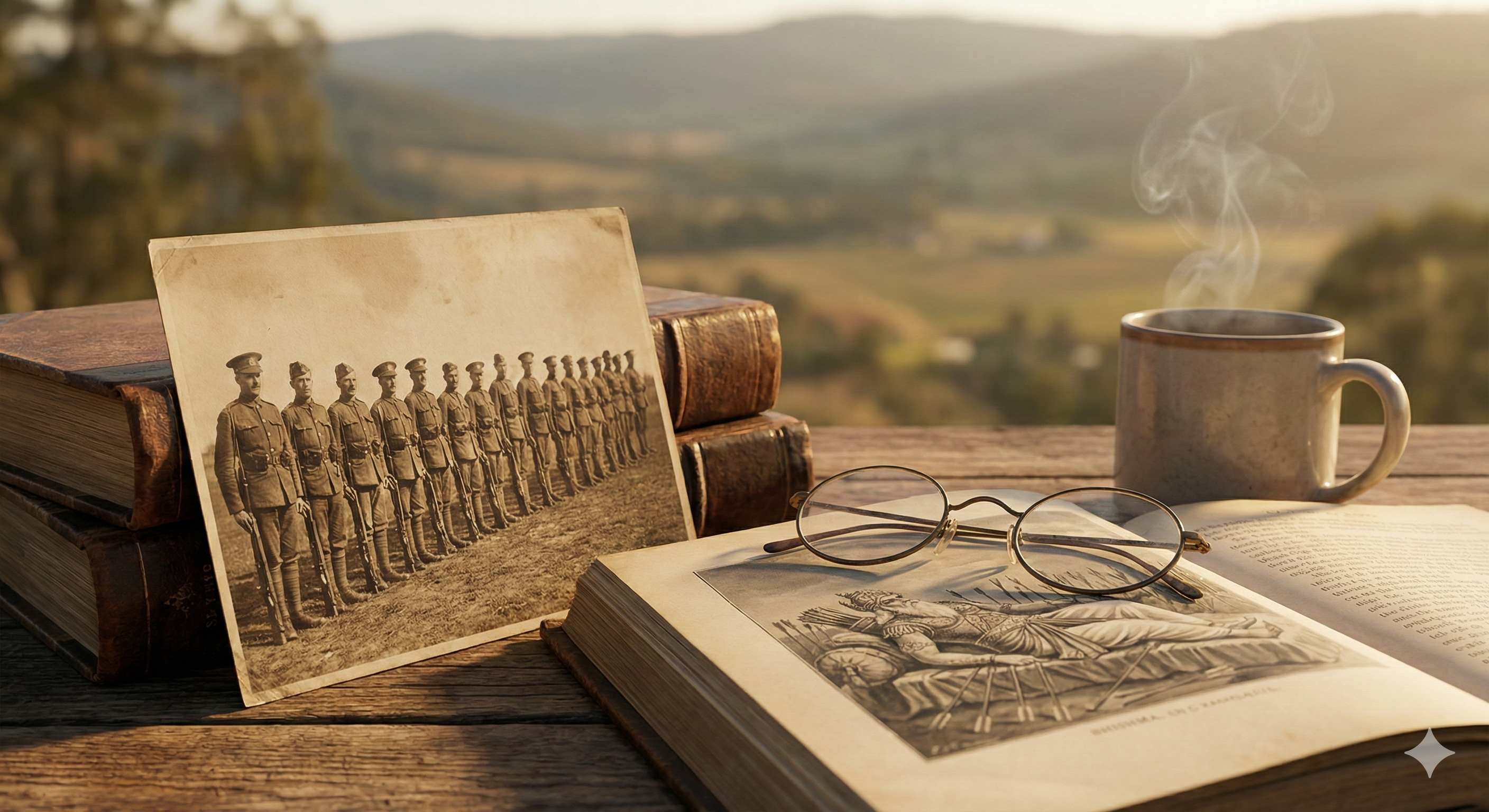

By late morning the question had settled itself into the gentle slopes of my thinking, neither demanding nor retreating, simply existing in a way that coloured the quietness of the day. I sat with the photograph again, noticing this time not the symmetry of the formation but the quality of the stillness in the men. It was the stillness of people learning to suppress the small movements of self — the tilt of a head, the shift of weight, the private impulses that normally accompany being alive. To stand as they stood required a certain discipline, a yielding of the inner voice to the cadence of a command. Courage might come later, in more difficult moments, but obedience arrived first, and that obedience held them now in place.

As I watched them, the distinction between courage and obedience began to crystallise. Courage belongs entirely to the person who feels fear and acts anyway; it is intimate, solitary, even when performed in a group. Obedience, on the other hand, exists only because another voice has been given the authority to guide one’s actions. The two are often entwined in the life of a soldier, but they are not the same thing. And I found myself wondering how much of what we call nobility in the armed forces comes from a confusion of these two qualities — how often obedience is praised when it is courage that deserves the tribute, or how often obedience is demanded when courage might have required resistance.

The thought deepened as the afternoon wore on, and memories of old stories drifted into it without any purposeful summoning on my part. The Mahābhārata, that vast and restless ocean of human motives, offered its lessons readily. Arjuna standing on the battlefield, suddenly unable to raise his bow — not because he lacked skill or fortitude, but because he recognised the moral entanglement of his situation. His doubt was not a sign of weakness; it was the clear, piercing moment in which a person recognises that duty, when separated from justice, becomes an instrument of harm. Krishna’s counsel to him has been interpreted in many ways, but its essence lies in the restoration of clarity, not the suppression of conscience. Only a wise charioteer can pull a warrior back from the edge of moral confusion.

But even as I recalled this scene, I found myself thinking of another figure from the same epic, one whose presence had always struck me as both reassuring and unsettling: Bhishma, the grandsire whose vow defined his life far more than his wisdom did. As a child I had admired him without reservation — his discipline, his loyalty, his unmatched command of warfare — but as the years passed, his story acquired a different hue. The same vow that made him formidable also made him vulnerable, binding him to a throne whose heirs descended steadily into pettiness and cruelty. When the great war finally came, Bhishma stood on the wrong side — knowingly, almost helplessly — not because he misread the moral landscape, but because he had allowed his obedience to an oath to outweigh his obligation to justice.

It occurred to me then that Bhishma is the purest embodiment of the dilemma that had been troubling me since morning. His tragedy is not that he was a bad man; it is that he allowed the purity of his intention to imprison him in the service of those who did not deserve his loyalty. The epic does not condemn him — it gives him pages of respect and a bed of arrows for his departure — but it shows, with heartbreaking clarity, the cost of surrendering judgment completely. Bhishma becomes a warning carved into narrative: even the noblest man may find himself upholding the cause of the unworthy if he hands his conscience over to an authority unexamined.

The valley was still in the afternoon heat, but the thought that came to me then felt like a breeze cutting through it. I realised that the soldier in the photograph, standing straight under a command that was not visible to me, was in some distant sense a descendant of Bhishma — bound not by a vow of celibacy but by the modern vow of obedience, ready to serve, ready to trust, and yet entirely dependent on the character of those who would command him. In that recognition lay the quiet beginning of something heavier: the understanding that courage, no matter how noble, can be misdirected by those whose wisdom is insufficient.

Continue to Part 3.